Sitting on a wooden jetty in the center of a pond in Oneida, New York, Cross Island Chapel might be the smallest house of worship on Earth. The clapboard structure measures less than 29 square feet and seats two parishioners. At the other end of the spectrum is the Great Mosque of Mecca in Saudi Arabia. Remarkably, it accommodates half the population of Los Angeles—4 million people.

Houses of worship from Cross Island Chapel to the Great Mosque of Mecca face security challenges that are distinct from any other type of facility. Many proudly want to keep their doors open to not only hold services but also to teach in-person religious school and host significant events such as baptisms, confirmations, funerals, weddings, shadada ceremonies, and bar mitzvahs. Religious institutions often serve as ambassadors to the community, welcoming support groups, clubs, youth activities, lectures, and political addresses. Houses of worship invite people to be their most vulnerable. But reality often intrudes.

Incidents of arson, vandalism, and destruction are distressingly frequent. Hate crimes at houses of worship increased by more than 33 percent between 2014 and 2018, according to the FBI. Almost 4,500 churches and Christian buildings have been attacked in the last year. The ACLU documented about 350 anti-mosque incidents in the United States between 2005 and 2020. In 2019, Jewish institutions were targeted 234 times, according to the Anti-Defamation League. Black churches have been in the crosshairs of white supremacists and other racist groups.

The age-old question is how to serve as a place of community, celebration, and sanctuary while balancing the need to protect worshipers, clergy, staff, students, and visitors.

The need is particularly acute. Brivo data show that houses of worship are just starting to reopen after the pandemic. Coastal cities such as New York (32.9% open), San Francisco (42% open), and Washington (57.4% open) lag behind more aggressive cities in the southwest such as Salt Lake City (83.5% open), Austin (71.1% open), and Oklahoma City (70.6% open).

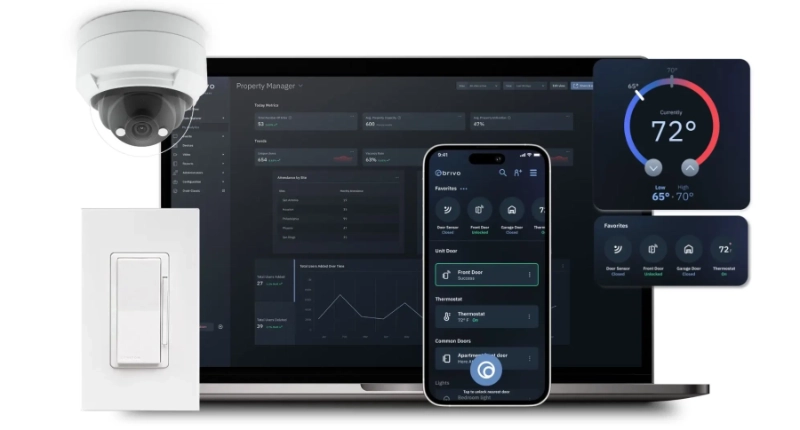

Physical measures such as access control solutions, video surveillance, and bollards all have their place in a well-rounded protection plan. Some institutions have used the yearlong pandemic pause to install multipurpose access control solutions, to include fingerprint entry, mobile access, and/or facial recognition for regular congregants and staff. In some cases, they have been able to repurpose existing hardware for their new solutions.

Mobile-based technology also provides occupancy data to show traffic flow and space utilization and to assist in de-densification efforts. Video intercoms at entrances allow staff to remotely unlock entrances and not have to constantly walk to the front door. With houses of worship limiting staff levels due to Covid, a single person may be greeting visitors, running the Skype feed of a service, and performing back-office functions. Remote management is crucial.

Central to securing temples, churches, mosques, synagogues, and other houses of worship are its congregants and members. Members and worshippers don’t want to contemplate danger. But an effective security stance for any religious facility begins with situational awareness, both in terms of physical surroundings and cultural zeitgeist. Members of a Korean temple, for example, would be attuned to regional anti-Asian sentiment, while synagogue congregants would take special note of regional white supremacy rallies, for example.

Clearly communicated policies and procedures must accompany situational awareness. Are emergency exits well marked? Are the pews stocked with instructions on what to do in a crisis, such as a fire? Do members know what to act if someone seems out of place or is behaving suspiciously? Is there a well-disseminated protocol for medical emergencies, power outages, and other crises? Do members know who to relay concerns to and where to seek help?

After a series of successful and attempted attacks on synagogues in Pittsburgh, Los Angeles, Poway, Pueblo, Miami Beach, and elsewhere, many Jewish institutions beefed up security with off-duty police and private security. Perhaps more important, though, has been to pair these officers with front-door greeters and sanctuary ushers. These volunteer members serve quadruple duty: welcoming members and guests to initiate a positive community experience; providing personal access control; identifying unusual people and behaviors and referring issues to security; and assisting in emergencies.

Increased threats and the pandemic have made religious institutions rethink their role in providing space to other organizations. One risk is loss of key control. Cardkeys and metal keys can be passed around and duplicated. Modern access control solutions, especially those with occupancy, traffic flow, and presence tracking (and integrated with technology such as video surveillance and intercoms), limit those concerns and allow houses of worship to be generous neighbors.

House of worship security is complex and multifaceted, but good resources exist. FEMA offers generous grants for target hardening, $180 million in 2021 alone. ASIS International’s Houses of Worship Committee has a best-practices guide for houses of worship security. Both FEMA and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Center for Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships have developed preparedness, response, and recovery tools.

Various communities offer their own resources. The National Organization of Church Security and Safety Management, based in Texas, delivers tactical and classroom training and hosts an annual conference. The Worship Security Association makes available videos on topics such as verbal de-escalation. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints shares its “Security Guidelines for Church Meetinghouses” with member institutions. Among the groups assisting the Jewish community are the Secure Community Network and the Anti-Defamation League. To protect mosques and their worshippers, organizations such as the Council on American-Islamic Relations, the UK-based National Mosques Security Panel, and the Islamic Society of North America.

Few religious facilities can isolate themselves via moat, a la Cross Island Chapel. But that isn’t necessary. The foundation of effective security is a combination of technology, people, policies, and procedures.

BRIVO + Camio

Learn about the Camio integration